Oscillations and Waves: Winter-2026

HW 1b (SOLUTION): Due W1 D5

- Fourier Series of a Triangle Wave

S1 5476S

Consider the following triangle wave:

- Find the Fourier series for a triangle wave (such as the one shown in the figure), which has amplitude \(A\) and period \(T\).

Examining this function graphically reveals some interesting properties that you can use to reduce the number of calculations you need to make. I will discuss that reasoning here, so you can learn how to do it. But, if you don't notice any of these features, you will still get the right answer, you'll just have to do more work.

First, the function has as much area above the horizontal axis as below, which means the average value of the function is zero and therefore \(a_0=0\).

Next, the function is symmetric about the point \(t = T/2\), which is a feature shared by the cosine terms in the Fourier series. We can guess, therefore, that all the sine coefficients will vanish.

Next, you will need to turn the graph of the function into an algebraic expression for the function:

The following integral will be helpful (you can derive it using integration by parts): \begin{align*} \int_{0}^{T / 2} t \cos( n \omega t) dt &=(\cos( n \omega)-1) / n^{2} \omega^{2}\\ &=\left((-1)^{n}-1\right) / n^{2} \omega^{2} \end{align*} Notice the role of the factor \(\left((-1)^{n}-1\right)\), which says that every other term is zero (whenever \(n\) is even).

The Fourier series will take the form: \begin{equation*} f(t)=A_{0} / 2+\sum_{n=1}^{\infty}\left(A_{n} \cos (n \omega t)+B_{n} \sin (n \omega t)\right) \end{equation*} \begin{align*} A_{0}&=\frac{2}{T} \int_{0}^{T} f(t) d t\\ &=\frac{4}{T} \int_{0}^{T / 2}(-4 A t / T+A) d t\\ &=\frac{4 A}{T}\left[-2 t^{2} / T+t\right]_{0}^{T / 2}=0\\ A_{n}&=\frac{2}{T} \int_{0}^{T} f(t) \cos (n \omega t) d t\\ &=\frac{2 A}{T}\left[\int_{0}^{T / 2}(-4 t / T+1) \cos (n \omega t) d t+\int_{T / 2}^{T}(4 t / T-3) \cos (n \omega t) d t\right] \end{align*} Because \(f(t)\) is a piecewise function, it is necessary to split up the integral into a left half and a right half. To reduce the algebra, you can recognize that the left and right integrals for the cosine terms will be equal in value! \begin{equation*} A_{n}=\frac{4 A}{T} \int_{0}^{T / 2}(-4 t / T+1) \cos (n \omega t) d t=\frac{4 A}{T}\left[-\frac{4}{T} \frac{(-1)^{n}-1}{n^{2} \omega^{2}}+0\right]=\frac{4 A\left(1-(-1)^{n}\right)}{n^{2} \pi^{2}} \end{equation*} Note that this coefficient is equal to zero for even values of \(n\), and nonzero for odd values of \(n\). This behavior is common in Fourier series. Once you have done a lot of them you can start to see the features that will lead to this behavior in the original function! (In this case, it is the linear dependence of \(f(t)\) on \(t\).) We could follow a similar procedure for \(B_n\), but when we get to the point where we break the integral up into two pieces, notice that the integral of the left side will be equal in magnitude but opposite in sign to the integral of the right side, and thus the full integral is zero. Therefore, \(B_n = 0\) for all \(n\).

The final Fourier series is therefore: \begin{equation*} f(t)=\sum_{n=1}^{\infty}\left(\frac{4 A\left(1-(-1)^{n}\right)}{n^{2} \pi^{2}} \cos (n \omega t)\right) \end{equation*}

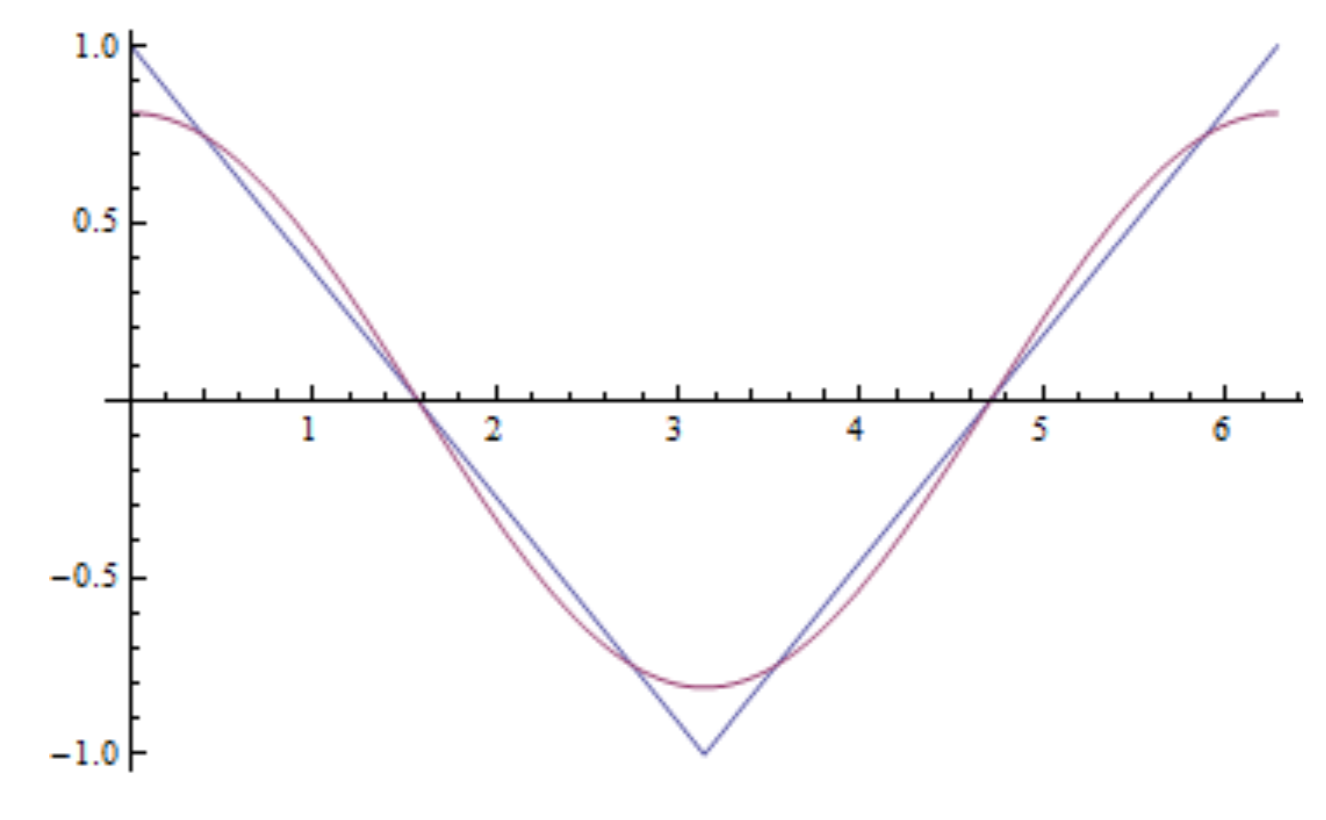

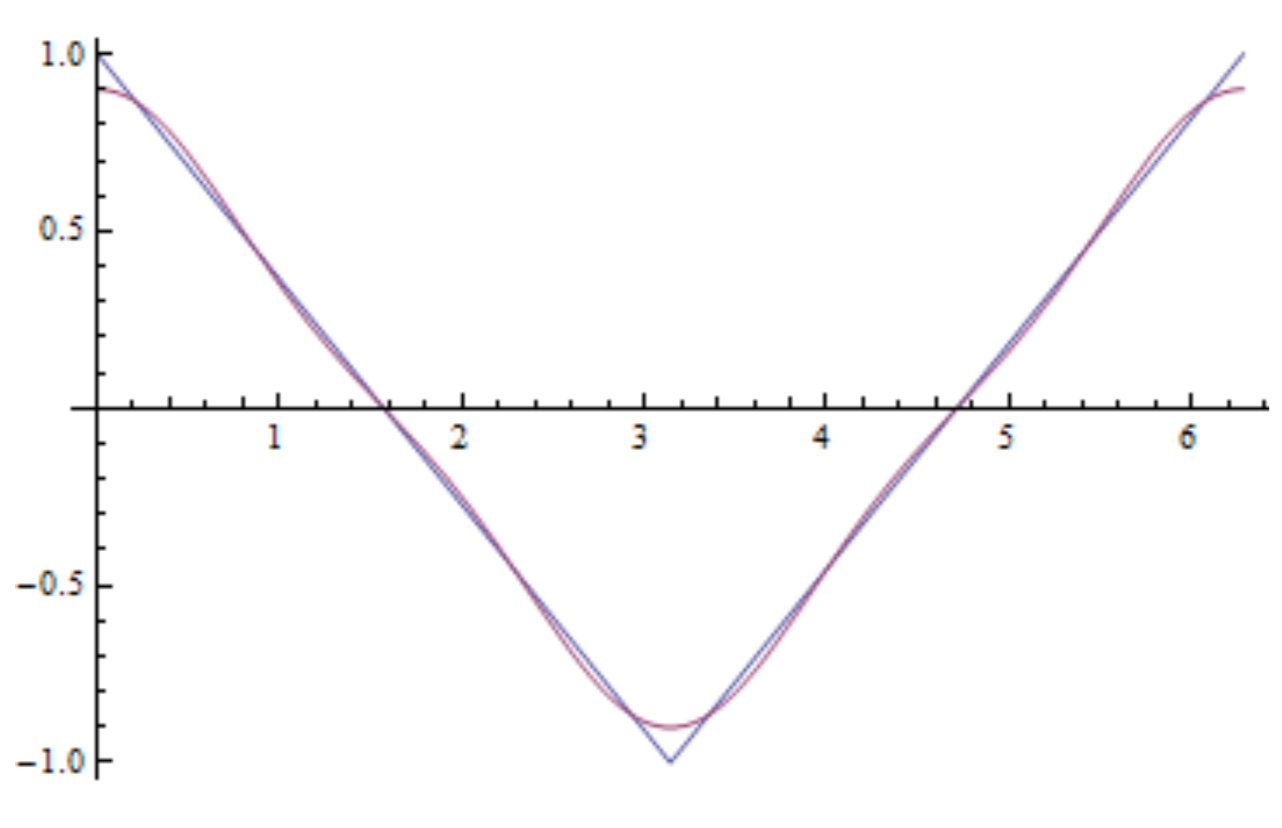

Plot two approximations to your solution, one including the first nonzero term and the other including the first four nonzero terms.

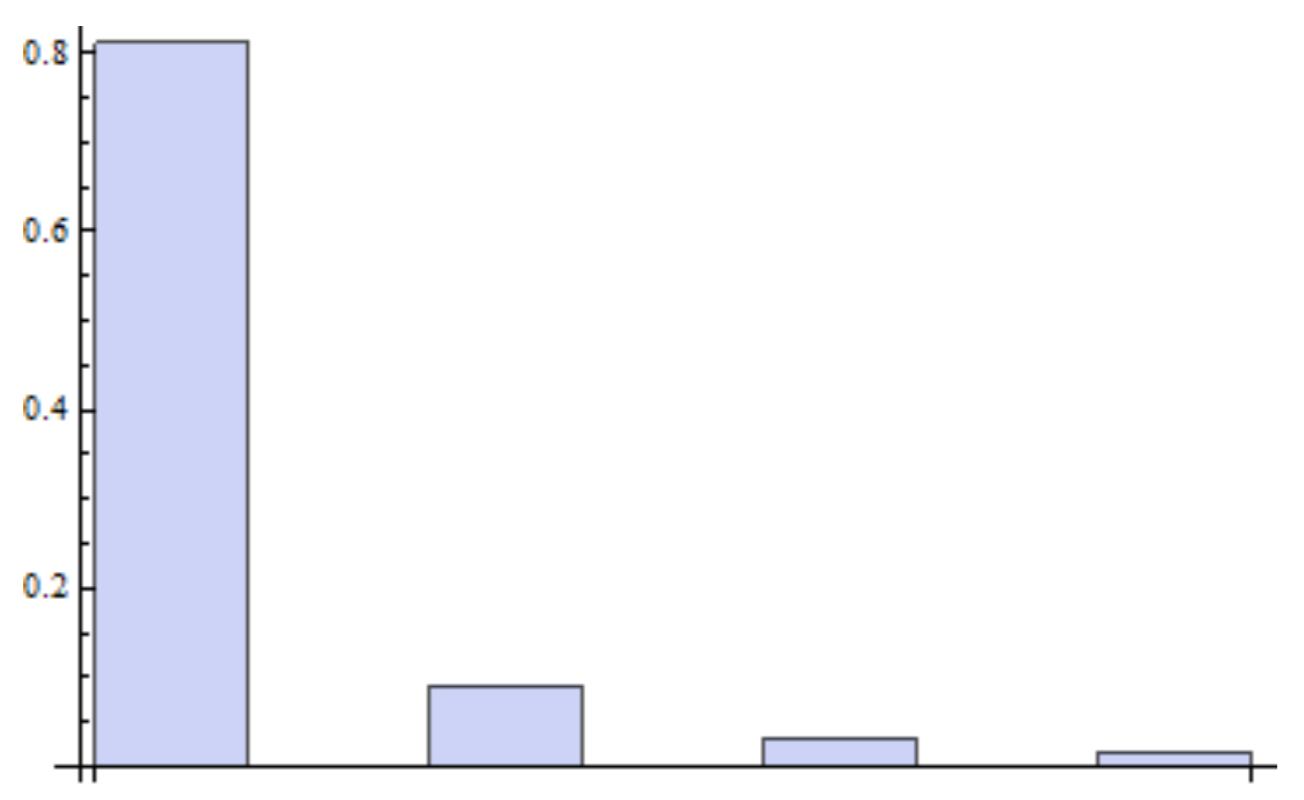

Make a histogram of your coefficients, i.e. find the spectrum.

- Find the Fourier series for a triangle wave (such as the one shown in the figure), which has amplitude \(A\) and period \(T\).

- Homogeneous Linear ODE's with Constant Coefficients

S1 5476S

Homogeneous, linear ODEs with constant coefficients were likely covered in your Differential Equations course (MTH 256 or equiv.). If you need a review, please see:

Constant Coefficients, Homogeneous

or your differential equations text.

Answer the following questions for each differential equation below:

- identify the order of the equation,

- find the number of linearly independent solutions,

- find an appropriate set of linearly independent solutions, and

- find the general solution.

\(\ddot{x}-\dot{x}-6x=0\)

Order: The highest derivative that appears in this ODE is a second derivative, so the equation is second-order.

Number of Independent Solutions: Thus, there are two linearly independent solutions.

Independent Solutions: I will make the Ansatz \(x(t) = e^{\omega t}\), find possible values of \(\omega\), and then write a general solution that is equal to an arbitrary superposition of the independent solutions. \begin{align*} \omega^{2}e^{\omega t} - \omega e^{\omega t} - 6e^{\omega t} =& 0 \\ \left(\omega - 3\right) \left(\omega + 2\right) =& 0 \end{align*}

The two independent solutions are therefore \(x_{1}= e^{3t}\) and \(x_{2}= e^{-2t}\).

General Solution: \(x = Ae^{3t} + Be^{-2t}\).

- \(y^{\prime\prime\prime}-3y^{\prime\prime}+3y^{\prime}-y=0\)

Order: The highest derivative that appears in this ODE is a third derivative, so the equation is third order.

Number of Independent Solutions: Thus, there are three linearly independent solutions.

Independent Solutions: I will use the same procedure as in the previous part, starting with the Ansatz \(y(x) = e^{k x}\). \begin{align*} k^{3}e^{kx} - 3k^{2}e^{kx} + 3ke^{kx} - 3e^{kx} =& 0 \\ \left(k-1\right)^{3} = 0 \end{align*}

There is only one solution to this equation, giving \(y_{1}\left(x\right) = e^{x}\). However, I must be able to find two additional (linearly independent) solutions (because this is a third order differential equation). The extra solutions can be found by multiplying the above solution by successively higher powers of x. This gives \(y_{2}\left(x\right) = xe^{x}\) and \(y_{3}\left(x\right) = x^{2}e^{x}\).

General Solution: \(y\left(x\right) = Ae^{x} + Bxe^{x} + Cx^{2}e^{x}\).

- \(\frac{d^2w}{dz^2}-4\frac{dw}{dz}+5w=0\)

Order: The highest derivative that appears in this ODE is a second derivative, so the equation is second order.

Number of Independent Solutions: Thus, there are two linearly independent solutions.

Independent Solutions: I will use the same procedure as in the previous parts, starting with the assumption that \(w\left(z\right) = e^{k z}\). \begin{align*} k^{2}e^{kz}-4ke^{kz} + 5e^{kz} =& 0 \\ k^{2}-4k+5 =& 0 \\ k = 2 \pm i \\ \end{align*}

The last step was done by applying the quadratic formula. The solutions to this equation are \(\omega_{1}\left(z\right) = e^{(2+i)z}\) and \(\omega_{2}\left(z\right) = e^{(2-i)z}\).

Or, you can equivalently write the imaginary exponential part in terms of sines and cosines using Euler relations:

\[\omega_{1}\left(z\right) = e^{2z}(\cos{z}+i\sin{z})\]

\[\omega_{2}\left(z\right) = e^{2z}(\cos{z}-i\sin{z})\].

You can even choose a different set of linearly independent solutions such that one is cosine (and entirely real) and the other is sine (and entirely real) by either adding or subtracting the above solutions (and dividing by a constant):

\[\omega_{+}\left(z\right) = [\omega_{1}\left(z\right)+\omega_{2}\left(z\right)]/2 = e^{2z}\cos{z}\]

\[\omega_{-}\left(z\right) = [\omega_{1}\left(z\right)-\omega_{2}\left(z\right)]/2 = e^{2z}\sin{z}\]

General Solution: Either of these two sets may be used for the superposition that gives the general solution, with different undetermined coefficients: \begin{align} \omega\left(z\right) &= Ae^{(2+i)z}+Be^{(2-i)z}\\ &= Ce^{2z}\sin{z} + De^{2z}\sin{z} \end{align}